Process Used to Develop the GER Framework

The project was a community-engaged iterative process that involved multiple steps of creating, sharing, getting feedback, and revising (Figures 1 and 2).

Themes Defined by Literature Review and Community Input

An initial step in the process was to identify themes that have the potential to impact undergraduate teaching and learning.

The GER themes were informed by a range of reports, discussions, and surveys including: focus group discussions at the 2015 GER workshop, results from the 2017 GER Survey, the DBER Report (NRC, 2012), the Wingspread workshop Report (Manduca, Mogk, & Stillings, 2003), the Earth and Mind II Synthesis report (Kastens & Manduca, 2012), and Lewis & Baker (2010). The Wingspread and Earth and Mind II reports emphasized themes of research on conceptual learning, geocognition, and instructional design, all largely under the umbrella of research on the development of geoscience expertise. In contrast, Lewis and Baker's "Call for a New Geoscience Education Research Agenda" emphasized research on K-12 teacher preparation, pipeline issues of attraction of under-represented groups to the geosciences, and on motivation and institutional support factors that affect these populations (Table 2). The DBER Report was more broad in scope, identifying several education research themes that cross STEM disciplinary fields, but not addressing either of these special populations. The 2015 GER workshop was a preliminary exploration of the comprehensive set of themes that emerged out of the earlier resources. Outcomes from the 2015 GER workshop highlighted the potential value of an additional theme on geoscience teaching in the context of societal problems, which was included along with K-12 teacher education as a themes for the community to give feedback on in the 2017 online GER survey.

Iterative Process of Community-Engaged Project Activities

Initial Community Survey and Webinar

The 2017 online GER survey was the first of a series of community-engaged activities in this project. The purpose of the survey was to share tentatively defined themes, and develop an initial database of important developments, recommended resources, and important research questions for each of the themes. Survey respondents (n=66, Figure 3) recommended ~100 resources related to the themes. Their comments highlighted the varying scale and scope of prior work done in different theme areas, the need for greater awareness and collaboration between GER and other STEM Education research fields, the need for better grounding of research in theories, and the need for stronger research design and assessment. Results demonstrated interest in all themes, with the greatest interest in cognition topics, instructional strategies, conceptual understanding, and teaching the Earth in the context of societal problems (confirming the decision to create this new research theme area). While prior reports (Table 2) emphasized research on conceptual understanding and on cognition research, the 2017 GER survey results suggest it would be valuable to make thematic distinctions between different sub-areas of conceptual understanding (Table 2, WG1 and WG2) and different sub-areas of cognition (Table 2, WG6 and WG7). In particular, although there is widespread interest in teaching with an Earth system science perspective, much of the published research in students' conceptual understanding lies in geology/solid Earth concepts. Creating a theme for the other Earth system "spheres" highlights their importance as areas of future geoscience education research. Survey results were reported to the community in a webinar and informed the program development of the 2017 GER workshop.

![[creative commons]](/images/creativecommons_16.png)

EER Grand Challenges and Strategies Workshop

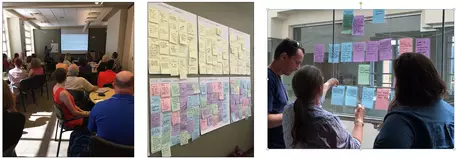

A critical step to facilitate action towards the project goal was a multi-day workshop of 46 geoscience education researchers at the 2017 Earth Educators Rendezvous. Prior to the face-to-face workshop, 10 working groups were defined, one for each GER themes (Figure 1). Applicants were matched to the thematic working groups, and working group leaders were nominated and selected based on experience and expertise for that theme. Working groups had 3 to 5 members. Participants included geoscience education researchers at different stages in their career and different types of institutions.

The expectations of the workshop were high, and working groups were tasked with defining an initial set of 3-5 grand challenges for their theme, a rationale for those challenges, and preliminary strategies to address those challenges. The grand challenges were to be in the form of well-justified, large-scale research questions that could, and should, guide future research for the GER community, and the recommended strategies were to be ideas on how the GER community could make significant progress on those important research questions, given their knowledge of the GER landscape.

To support this effort, the workshop was structured to include focused working group time, opportunities for working groups to share and get feedback from other participants, and two whole-group cross theme sessions, the topics of which emerged out of the earlier survey (Table 3 and Figure 4). Working groups had access to recommended resources submitted from survey respondents, as well as resources recommended by project leaders and submitted pre-workshop by working group members.

Engaging with the Broader Community: Opportunities to Share and Get Feedback

In order to ensure broad community input, there were opportunities for sharing with and getting feedback from outside the working groups at different stages in the GER Framework development process. The largest of these was the EER Geoscience Education Research and Practice Forum, which attracted ~140 geoscience educators and researchers. The purpose of the Forum was for researchers to listen to educators' ideas on what questions they would most like geoscience education researchers to address on their behalf. Educators divided into small discussion groups organized around the GER theme areas, with one or more working group researchers present in each small group. Discussions were rich; this provided an opportunity to identify promising practices and puzzling questions that are important and suitable for research, as well as a means of gauging alignment of ideas on what educators think is important to address with ideas that GER working group members were already generating on grand challenges. Feedback from the Forum influenced the evolution of the draft grand challenges and raised the awareness among GER working group members of educators' interests, concerns, and priorities.

By the close of the EER GER workshop, a preliminary set of theme-based GER grand challenges and supporting strategies was produced. A GSA Townhall meeting was organized as the first opportunity to publicly share and vet these draft Framework materials. It was attended by ~50 people. Representatives from each working group gave a "lightning" 1-2 slide presentation on their GER theme, and then attendees had the opportunity to visit and write notes on theme posters (Figure 5) which listed all of their grand challenges and had space for adding critiques, ideas on prioritization, and suggested strategies. In addition, more traditional outlets of conference presentations were also used as ways to share ideas and get feedback; these included posters at GSA (poster accessible online) and AGU meetings, and an oral presentation at the AMS meeting (recorded presentation accessible online).

Following the GSA Townhall, working group leaders and contributors from their teams revised the grand challenges, and expanded upon the rationales and strategies so that by the start of the AGU meeting each theme had a full draft ready for critical review by the broader community. This was facilitated through a 2-month Open Comment Period. Draft GER Framework materials (at this point referred to as theme "chapters") were hosted on a SERC website; comments could be entered in 'Discussion' boxes directly on the webpages for each of the 10 theme chapters. Efforts to alert and encourage community members to contribute their comments included distribution of flier (with a QR code to the webpage) at the AGU NAGT booth and at the project poster, notices in the NAGT newsletter, the NAGT GER Division newsletter, the GSA Geoscience education listserv, direct emails to attendees of the 2015-2017 EER GER workshop attendees, authors that published articles in the JGE theme issue on Synthesizing Results and Defining Future Directions of GER, and other members of the GER and geoscience education community. In sum, comments from 40 people were submitted; 67% of these were from geoscience educators and researchers external to the project, and the remaining comments were from those internal to the project but from other working groups than the themes they critiqued. Each theme chapter received comments from 3 to 5 reviewers. Reviewers provided substantial feedback, on par with the thoughtful constructive comments expected on manuscripts submitted for peer-review. These comments helped chapter authors recognize and address gaps, refine the ideas communicated, and better situate the grand challenges and recommended strategies in a meaningful context.

![[reuse info]](/images/information_16.png)