In the Field

Field research experiences can be defining moments in people's careers. For geology undergraduate majors they are also required; 99% of the 300 geology undergraduate majors at U.S. institutions surveyed in 2008 required a field course (Drummond and Markin 2008). Time in the field can inspire students to pursue a career in research. On the other hand, unsafe field environments can have devastating personal and professional consequences. Identifiable conditions contribute to unsafe field environments where harassment, bullying, racism and discrimination can occur. We present recent research on how to ensure safe, accessible and inclusive field experiences, which center on the adoption and enforcement of rules for appropriate behavior.

What do we mean by "in the field"?

Field environments pose unique challenges:

- new, unfamiliar, unknown or nonexistent rules of conduct and reporting mechanisms;

- reduced independence for access to transportation, food, medical resources, etc.;

- distance from personal support networks at home;

- unfamiliar cultural norms or language;

- long days with physically strenuous work and exhaustion;

- exposure to harsh environmental conditions and potential greater risk of environmental hazards, or unfamiliar risks compared to the home base location.

See John, C.M. and S.B. Khan. 2018. Mental health in the field. Nature Geoscience 11: 618–620 for a description of factors that can affect stress and mental health in the field and strategies to increase positive outcomes.

In many disciplines, there is also a culture of Vegas Rules ("What happens in the field, stays in the field"), with expectations of people behaving differently than would be acceptable at home. Existing power dynamics that are clearly defined on campus or in the office can become blurred with the common practice of shared living accommodations, that may also afford little privacy, in the field, and remove the clear boundaries between work and personal lives. Power dynamics can also become more stark, with one person holding access to the keys to the vehicle or satellite phone. On top of this, enduring harsh, rugged conditions is often considered a rite of passage, to the exclusion of anybody who does not fit the image of what a "real field scientist" looks like. While to many, camping and hiking are fond childhood memories, field experiences can be intimidating and stressful to people with limited exposure to the outdoors, whether for cultural, economic, accessibility or many other reasons. These factors and cultural norms contribute to the persistent low diversity in disciplines like the geosciences. In many parts of the U.S., people of color also experience racial and life-threatening harassment from members of communities where they are doing fieldwork.

See: Barriers to fieldwork in undergraduate geology degrees by Giles et al. 2020.

In this context, harassment, bullying and discrimination create an unsafe environment and hence become a safety concern.

Read about some of these challenges in our paper Hostile climates are barriers to diversifying the geosciences

Harassment, bullying and discrimination in the field

In a recent survey of field training, 64% of respondents stated that they had personally experienced sexual harassment and over 20% reported that they had personally experienced sexual assault. Over 90% of women and 70% of men were trainees or employees at the time of the incident (Clancy et al. 2014).

- Anonymous survey respondent in Nelson et al. 2017

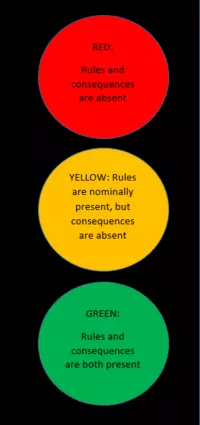

A follow up to the SAFE study to learn about how fieldwork experiences can affect career trajectories revealed large variability in clarity of rules and appropriate conduct for field research and training contexts (Nelson et al. 2017). Incidences of sexual harassment more often were associated with environments where rules and behavioral standards were not clearly codified and consequences for misconduct were not enforced. Conditions that allowed for sexual harassment to occur also contributed to other hostile environments, with gendered divisions of labor, outright sexism, abuses of power, and dismissal of individuals' contributions to the work. These behaviors have long-term negative career consequences, such as reduced access to professional opportunities, career stalling, relocation to a different institution or field site, or leaving career paths altogether.

Inclusive Field

Exclusionary behaviors can have especially injurious effects in disciplines with low diversity, like the geosciences. Historical exclusion of people of color from many academic disciplines and science professions has led to low representation. This is known to lead to professional and social isolation, which can render individuals more vulnerable to hostile behaviors. A recent survey revealed that 40% of women of color reported feeling unsafe in the workplace because of their gender or sex, 28% reported feeling unsafe because of their race; and 18% reported skipping professional events, including fieldwork, because they did not feel safe (Clancy et al., 2017).

- Lauren G., Camping While Black

Awareness of how groups with different visible identities are perceived and treated by others in different environments is key for ensuring safe and inclusive field experiences.

To learn more about how gender, sexual orientation, and racial and ethnic identity shape experiences in the field:

- Scientists push against barriers to diversity in the field sciences by J. Pickrell. Published March 11, 2020.

- Amon, D.J. Z. Filander, L. Harris and H. Harden-Davies. 2022. Safe working environments are key to improving inclusion in open-ocean, deep-ocean, and high-seas science. Marine Policy 137: 104947

- Birding while Black by J.D. Lanham. Published September 22, 2016.

- Environmental experiences have racial roots by S. Pierre. Published June 15, 2017.

- Dowtin, A.L. and D.F. Levia. 2018. The power of persistence. Science 360: 1142.

- White, E.C. 1996. Black women and the wilderness. In: B. Thompson and S. Tyagi (eds). Names We Call Home: Autobiography on Racial Identity. Routledge, New York, NY. Pp. 283-286.

- Outdoor Afro is a national non-profit organization with leadership networks around the country that promotes inclusion in outdoor recreation, nature, and conservation.

- A Revival of the Green Book for Black travelers by B. Mock. City Lab. Published April 2, 2018.

- The Challenges of fieldwork for LGBTQ geoscientists by A.N. Olcott and M.R. Downen. Published April 11, 2021.

- In fieldwork, other humans pose as much risk to LGBTQIA+ people as the elements by D. Haelewaters and A. Romero-Olivares. Published December 9, 2019.

- Transgender and non-binary scientists can also experience vulnerability in the field. Don't let them see you cry. A paleontology writer's experience of gendering - and misgendering- in the backcountry. by R. Black. Published November 30, 2021.

The University of Birmingham Earth Sciences Department (Greene et al.) has created a useful document with recommended best-practices for toilet stops in the field.

Check out a new resource on Menstruation in the field by B. Davies and B. McCerery.

Accessible Field

By Anita Marshall

Disability status intersects all other identities and it is important to consider ways in which to enable individuals with diverse abilities to safely and effectively take part in field work. As with all students, individuals with diverse abilities can be integral members of a field campaign when equipped with the tools and information needed to be successful.

Lack of information has been identified as a significant barrier for students with disabilities preparing for field work. Basic descriptions of terrain, physical requirements and facilities should be readily available for participants before going into the field. Students who are new to field work may not be aware of what aspects they need to discuss with trip organizers unless this information is available in advance. Further, you should be able to answer questions of accessibility regarding field equipment such as visual, auditory, and motor skills required to operate equipment.

Each individual is unique, and the best way to determine an inclusion strategy is to include the student(s) in discussions about potential barriers and approaches to inclusion. Communication is key. When crafting literature or materials about field courses, consider using language that assures the student it is in their best interest to discuss their needs in advance and that their needs will be taken seriously, and handled from the perspective of maximizing inclusion, rather than excluding participation.

To learn more about accessible field experiences:

- The International Association for Geoscience Diversity (IAGD) is a 401c3 non-profit focused on improving access and inclusion for individuals with disabilities in the geosciences. The forum-style website is designed to be a crowd-sourced resource for all topics relating to disability inclusion in the geosciences.

- For a personal account of the challenges of geology students with disabilities, see It's time to stop excluding people with disabilities from science.

- For examples of inclusive field experiences, see the article Geology for Everyone: Making the field accessible and the video The IAGD in Ireland: Exploring Approaches to Inclusive Field Geology. See also these case studies for inclusive field experiences for students with physical disabilities.

- Chronically Academic, a network of academics with disabilities and chronic conditions who provide mutual support and resources.

- See also: Carabajal, I.G. Marshall, A.M., & Atchison, C.L. 2017. A synthesis of instructional strategies in geoscience education literature that addresses barriers to inclusion for students with disabilities. Journal of Geoscience Education 65: 531-541.

Safety First

- leadership engaged in modeling appropriate behavior;

- open discussions of rules and codes of conduct;

- clearly defined rules;

- established protocols for reporting violations;

- defined consequences for misconduct.

Codes of conduct (rules) and accountability (enforcement of said rules) are critical to ensure safe and successful field work, which lead to positive experiences, greater productivity and equal opportunity in professional development (Nelson et al. 2017).

When preparing for the field, consider:

- What are the potential safety hazards and risks, including how people are treated?

- What is the plan for safety and does it include information on how to address harassment, bullying and discrimination?

- What is the conduct policy at the field site?

- Who is responsible for responding to a safety incident?

- What are the reporting mechanisms?

- How are conditions created and maintained that reduce all safety risks?

- What are the attitudes around alcohol and drug use at the field site and how may these interfere with field safety?

The National Association of Geoscience Teachers has more useful resources on field safety.

Check out resources from a 2021 NSF-funded Workshop to Promote Safety in Field Sciences and the final report.

Field Codes of Conduct

In addition to the elements outlined on our code of conduct resource page, effective policies for field environments should include:

- Protection for targets: protect their safety, allow them to continue their fieldwork with minimal disruption, protect privacy as much as possible.

- Always have an "out": all field workers must have access to transportation and communication devices whenever possible, with no gatekeepers.

- Always have multiple resources/avenues to contact help available for all involved and witnesses

- Encourage bystander intervention and reporting

Examples:

- Keck Geology Consortium handbook for faculty Program Directors participating in field experiences, including sections on Sexual Assault and Harassment and Non-Fraternization policy (and alcohol and drug abuse policies).

- University of Alaska Fairbanks Toolik Field Station Sexual Misconduct Policy

- Multi-institution aircraft field campaign WE-CAN Harassment Procedures

Go to our code of conduct resource page for more examples.

Resources and References

Guidelines and handbooks for inclusive and safe field experiences:

- Report of the Workshop to Promote Safety in Field Sciences (2022) by Anne Kelly and Kristen Yarincik

- Field Team Leadership: Strategies for Successful Field Work by Erin Pettit

- Leveling the Field – Tips for Inclusive Arctic Field Work by Sandy Starkweather, Kim Derry and Renee Crai.

- Toilet stops in the field: An educational primer and recommended best practices for field-based training. By Sarah Greene, Kate Ashley, Emma Dunne, Kristy Edgar, Sam Giles and Emma Hanson.

- GEO REU Handbook: A Guide for Running Inclusive and Engaging Geoscience Research Internship Programs, edited by Valerie Sloan and Rebecca Haacker

- Best Practices for Promoting a Safe, Educational, and Inclusive Atmosphere when Off-campus with Trainees by Georgia Tech School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences

- Ten steps to protect BIPOC scholars in the field by J. Anadu, H. Ali and C. Jackson. Published November 10, 2020.

- Safe fieldwork strategies for at-risk individuals, their supervisors and institutions by A-J. C. Demery and M.A. Pipkin. Published October 12, 2020.

- Safety and Belonging in the Field: A Checklist for Educators by Sarah Greene et al.

For more reading about field experiences:

- *TRIGGER WARNING* How to Take Care Anonymous post in Field Secrets: A Field Guide to Living in the Field blog. Published September 25, 2018.

- Joyce, K. Out here, no one can hear you scream HuffPost Highline. Published March 16, 2016.

- Gewin, V. 2015. Indecent advances. Nature 519: 251-253.

Surveys of sexual harassment and assault during field research and on campus reveal a hitherto secret problem. - Scholes, S. The Harassment Problem in Scientific Dream Jobs. Outside magazine. Published May 21, 2018.

Fieldwork in far-flung places is exciting and rewarding—until it's not. - Switek, B. The many ways women get left out of paleontology. Smithsonian.com. Published June 7, 2018.

- Looby, C.I and K.K. Treseder. Working in the field: New solutions for old problems. AWIS Fall 2015.

- Harassment, a field study Nature Ecology & Evolution Editorial 2017

- Hostile Environment by Krista Langlois. Published January 31, 2018

- Sexual harassment in research abroad. by Kathrin Zippel. Inside Higher Ed. Published March 31, 2017.

- Moylan, C.A. and L. Wood. 2016. Sexual harassment in social work field placements: Prevalence and characteristics. Journal of Women and Social Work 31: 405-417.

- Field sites are harassment hell. Here is how to improve them. by Nell Gluckman. Published July 15, 2018

References cited:

- Clancy, K.H. et al., 2017. Double jeopardy in astronomy and planetary science: Women of color face greater risks of gendered and racial harassment. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 122: 1610-1623.

- Clancy, K. et al., 2014. Survey of academic field experiences (SAFE): trainees report harassment and assault. PLOS ONE 9, e102172.

- Drummond, C.N. and J.N. Markin. 2008. An Analysis of the Bachelor of Science in Geology Degree as Offered in the United States. Journal of Geoscience Education 56: 113-119.

- Giles, S. et al., 2020. Barriers to fieldwork in undergraduate geology degrees. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment 1: 77-78

- Marin-Spiotta et al., 2020. Hostile climate are barriers to diversifying the geosciences. Advances in Geosciences 53: 117-127.

- Nelson, R.G. et al., 2017. Signaling safety: Characterizing fieldwork experiences and their implications for career trajectories. American Anthropologist 119: 710–722.